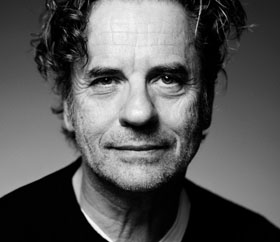

Alberto Venzago is a reportage photographer, photo artist, filmmaker; widely travelled, much admired, highly decorated. Always on the run, always looking for the next thing. And usually he finds it with unerring accuracy. With patience, perseverance and empathy, the winner of the Robert Capa Award has brought back images from places where you can’t really get to. Or where you want to go. Bookfactory CEO Christian Burkhardt spoke with Alberto Venzago about his life, his photographic world view and his projects. His major retrospective “Picture taking – Picture making” will open in May 2021 at the Museum für Gestaltung, Zurich. Exclusively for our readers, Alberto Venzago will give a guided tour of the exhibition. More information at a later date.

Alberto, let’s start right away with a “decisive moment”. You were a photographer at the legendary Magnum photo agency. It was co-founded by Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Cartier-Bresson in turn coined the meaning of the “decisive moment”, that is, the decisive moment that needs to be captured photographically. How do you capture the decisive moments?

Henri Cartier-Bresson was like my teacher – I looked at his contact prints at Magnum for 4 years. So I could see exactly how he thought, what drove him. Did he look at the object from all sides or was it just a “Lucky Punch”? That’s how I learned from him how he operates. This decisive moment often takes place in a thousandth of a second, similar to football. When the play opens, when everything comes together at once. In the photographic sense, that’s light and movement, facial expression, habitus..

…and the goal kick…?

…it clicks. The cheering I hear only in me, but I hear it louder.

Sounds pretty simple.

Beirut

It would be, too, if the right moment was usually not too early or too late. Then you might be waiting for a second chance or – Cartier-Bresson never said that – you need luck. I say: he who creates honestly deserves luck. Experience and intuition certainly help to force the luck. And you need to know your device. You must be able to manipulate in the dark, at any time. Film out, rewind, fast forward, focus goes to the left or right and so on. At 50 mm, I’m 1.60 meters away and then I have exactly the right detail in 35 mm format. It’s a flesh-and-blood thing. Just like the striker doesn’t think when he shoots. Because otherwise it usually goes wrong.

Watching movies in the dark sounds like old times. How about you – analogue or digital?

It’s all the same to me. I can also take pictures with a shoebox. Either you see the picture or you don’t.

Are there any cameras you particularly like to work with?

I like to work with Leica and the old lenses, that still has an analogue touch. Whether it’s in focus or not isn’t that important. I also work with Hasselblad, also digitally. I also love working with a Polaroid back, I find it very exciting.

The cameras of today are no longer just Leica or Hasselblad, but Apple, Samsung and Co. What do you think of smartphones as cameras?

I don’t photograph with a smartphone – I just like to have a camera between me and the subject. And I also like it when the camera is a bit bigger and heavier. My children do a lot of photography with smartphones, but the oldest one has now also started with analogue photography. That makes me happy, of course. With a Hasselblad, for example, you have 12 pictures, maybe x5, then you have 60 pictures – you have to think about where you can and want to shoot. This economization of the number of images increases the value of the individual image.

“You have to dive in before you shoot.”

Let’s take a jump, go out into the world and see your photos. It’s hard to list your many projects across all genres, including film in recent years, in one breath. How do you choose your projects?

The basic prerequisite is a topic that fascinates and fulfills you, and that you are convinced is important. Accordingly, the first question is: do I really want to do this, subordinate my life to it. Because kneeling down means giving absolute priority to the project. With all the ups and downs.

Yakuza

…and social life?

You have to be consistent. Family, love… doesn’t exist then.

What comes after that, how do you tackle the project?

The first requirement is a lot of research. Then you know if it’s really what you imagined. The more you learn about a topic, the more you learn if it is really what you want. Because you enter new territory when you leave your cultural area. You have to deal with other languages, other socio-cultural parameters. All this is contained in the rectangular picture that you look at later. So you take a photograph long before it even clicks. As a photographer and artist, you naturally want to do something that others may not have done before. For me, that also means being on location. To perceive the place with all your senses.

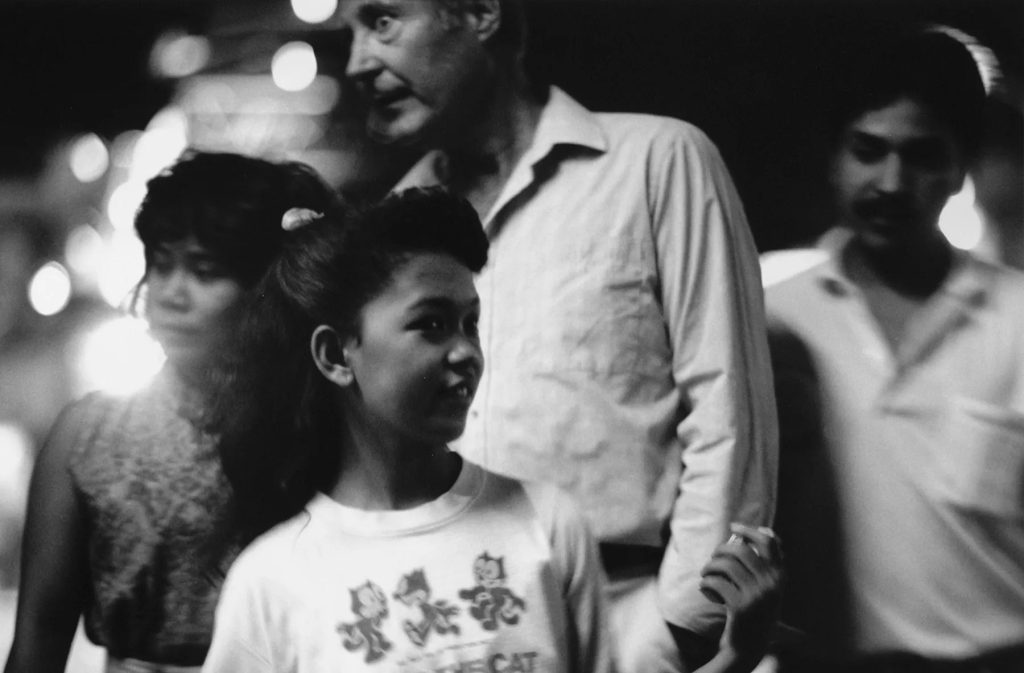

Your reportages, for example about the Yakuza in Japan, Voodoo in Benin, child prostitution in the Philippines, focus on sensitive topics. How did you find the access to the subjects?

It requires a huge portion of respect. With the big stories I didn’t photograph at all at the beginning. With Yakuza I didn’t even have a camera with me for the first six months. People rightly want to know who you are, rightfully so. Because there is no need for them to have their picture taken. They get no money for it. The only thing they get is my interest in their story. And that’s why it’s always about the personal relationship. Which you build up with sensitivity and respect. That means you must be willing to give and show a lot of yourself. You are a human being and have an environment that is perhaps similar to theirs. Speak family, existential fears and so on. The basis is mutual trust. You play with open cards.

Yakuza

That means you’re 200% in this project.

Yes. But I also need to know, am I safe there? In my voodoo project these were really important, basic questions: do I really want to go into that room without light and floor? Is that possible? I was bewitched, I had malaria twice, I was finished. So such an experience is also a physical challenge – it’s just not exactly behind the station…

The subject of research is one thing, but how do you approach people in general whose language you don’t speak, who don’t want or are not able to lead a classic bourgeois life and whom you want to photograph?

Sensitivity is the key. When I was in the Philippines to photograph child prostitution, I always had a female assistant with me. Because in the eyes of many people there I primarily look like a john – a white middle-aged European. And he only wants to take photos? My assistant and I looked like a couple. That helped to break down barriers and gain trust. But it’s also true that if it doesn’t work out, if someone doesn’t want to get involved with you or even wants to be photographed, then that’s the way it is. Respect and empathy means to respect the wishes of your counterpart. In yakuza culture, for example, tattoos are elementary. In order to photograph them, i.e. their naked skin, I had to show myself naked as well, otherwise it wouldn’t have been possible. Figuratively speaking, people want to look into your soul to be able to trust you.

Philippines

How do you see such slow processes of relationship building in today’s fast moving Instagram photo world?

Fortunately, this didn’t exist back then, so for lack of opportunities, there was no temptation at all to shoot on continuous fire and publish everything at the same moment. We are storytellers, and it takes time to experience and tell them.

…any advice to the young Instagram photographers?

I don’t want to give any advice. We are all children of our respective times. Perhaps just one thing: Take your time. You have to dive in before you take your shot. But the bottom line for me is, get out there and tell your story. It has to bring you added value, it has to make you happy, it has to give you sleepless nights – all your energy goes into it. The word impossible does not exist.

Voodoo

You are not only travelling solo, as a photographer and filmmaker, but also as part of the duo ONE, which you form with your life partner Julia Fokina. Your upcoming monumental work ONE – Seduced by Darkness will be produced by Bubu in oversize, 1 x 1.6m and in a very exclusive small edition – each book will be a 50kg unique specimen. How do you work together, how was the book created?

Julia is my life partner, my muse. And my partner in art. Working as a duo is something completely new for me, just like the book. I’ve always travelled around alone and suddenly you meet this woman. She is not only the one in front of the camera, but she brings a lot of ideas herself – we are a team. I’ve done a lot of crazy things before, but this is a different league now, something completely different.

You learn a lot from it.

Yes, my well-trained ego was dampened in the beginning because I suddenly had to share, to listen – it’s a thoroughly shared story. Sometimes I think something doesn’t work at all because I look at it from the technical side. But Julia has a completely different approach. That challenges me, I perhaps have to think about it once more and then we realize that it works. That’s teamwork – that’s new to me, and a very nice thing. The cooperation is incredibly intense: we live together, we are a couple, we are together a lot. It’s a great challenge in which love is a very important part.

ONE, Seduced by the Darkness

The first result of your collaboration is the monumental book Seduced by Darkness. It is obvious that you think on a large scale.

Absolutely. I’ve never made a book that has such a unique character – of course this has to do with my youthful optimism: it simply has to be big. And it is constantly changing, hence the unique character. We always make two books at the same time, and with each book there is always something new, about 20% of the pictures vary. All this is not a rush job, but should develop continuously. In the name ONE there is also the fact that we are not only photographers, we do everything: Research, implementation, post-production, printing, project management, sales… That’s the great thing about it: We are like a factory – everything comes from the same house. I think that’s great and I like that! It is also a craft!

So you exist in multiple forms, as photographer and filmmaker, as collaborator?

Exactly. Venzago himself goes on as usual. But with ONE my cosmos has expanded considerably. It’s like a creative journey on which something new constantly happens. What else is coming? I don’t know, but it will be good.

Alberto, thanks for the exciting conversation. Finally: If someone wants to start taking pictures, what advice would you give them?

My advice is: go to a museum. Not to a photo museum, but to a museum. Look at what the great masters have done. How they used light, how they worked out features or weakened them, etc. That’s where you learn the most! In the museum! There you have to learn to see properly.

Alberto Venzago

More information about Alberto Venzago, his projects,

the artist duo ONE and many pictures:

www.venzago.com

Cover image: ONE, Seduced by the Darkness